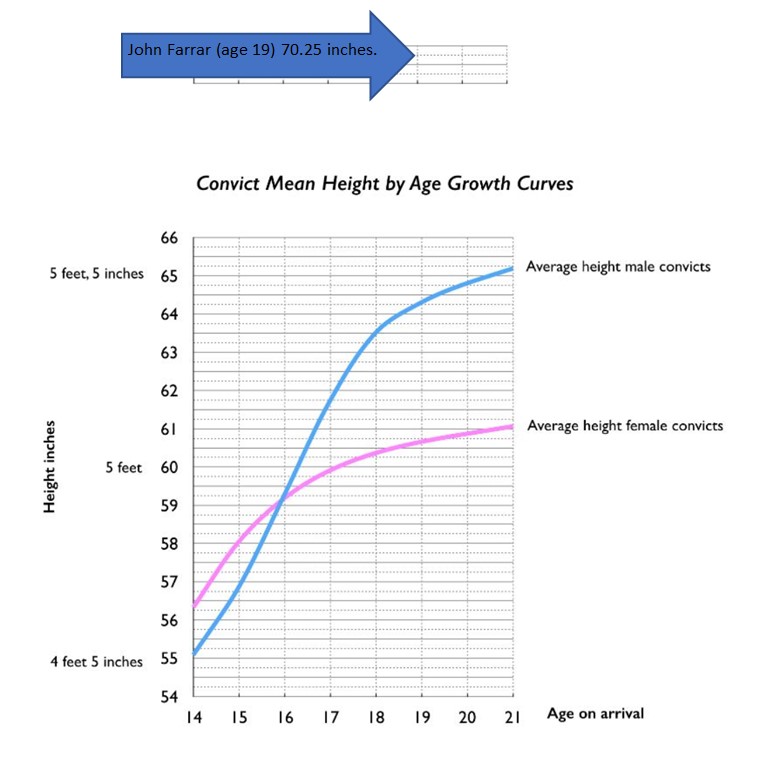

Figure 1: Convict Mean Height by Age Growth Curves – heights for convicts aged 21 or less on arrival in Australia. Includes John Farrar’s height. Hamish Maxwell-Stewart, ‘Height and Native Place’, HAA105, Module 3, Chapter 2, Accessed 29 May 2020.

John Farrar: A Convict in Context

By Kirstin Nicholson - the Family Tree Detective

In this essay I will look at the life of John Farrar who was transported to Australia in 1819. I will compare John’s life experience with his brothers, Joseph and Isaac, and the lives of other convicts who were transported around the same time and consider if they were typical or atypical.

Born in West Yorkshire in 1800, John Farrar was one of seven children, including Isaac and Joseph.[1] The brothers escaped conviction for burglaries until 1818 when they were sentenced to death for the burglary of an elderly couple.[2] The sentence was commuted to life transportation.[3]

In September 1819 John and Isaac arrived in Sydney on the John Barry (the same vessel that carried Commissioner Bigge).[4] Joseph followed in October.[5] Since 1815 the introduction of Surgeon-Superintendents ensured the convicts’ physical and mental wellbeing were looked after, so the Farrars were all ensured a healthier journey than those who had come just years before. Bigge believed that country convicts were better behaved, and healthier on the journey than their London counterparts.[6] Neither John nor Isaac is mentioned in the surgeon’s journal, perhaps there is truth to this.[7] Aged 19, John was 70.25 inches tall – he was the third tallest on the ship – the average 19-year-old male convict was 64.25 inches on arrival.[8]

Hyde Park Barracks opened months before the Farrars’ arrival and convicts now ‘lived’ at the barracks, leaving only for work.[9] Their activities and movements were regulated. Previously, convicts had freedom of movement between work hours, a luxury not enjoyed by the Farrars.[10]

Transportation numbers had risen considerably following the recent end of the Napoleonic Wars. Before then most convicts were distributed among free settlers and the government employed the balance. The increase created a surplus so the government established Emu Plains, and more gangs for road and bridge work.[11]

Before they had even arrived in Australia, their opportunities and life courses were already on a different path than those who had arrived just years before.

John was a cotton weaver in England, a trade not required in Australia.[12] He worked on road gangs in Sydney and Bathurst and became an overseer.[13] On vessels, authorities chose convicts who appeared intimidating for the overseer role. If this was the case in the colony, perhaps John’s height was a factor.[14]

John gained a ticket-of-leave, married and had three children.[15] One in four convict men married after arrival in Australia; John was in the minority.[16] In 1839 he absconded and his ticket-of-leave was cancelled.[17] No more is known about John until mention of his death in Joseph’s probate documents in 1850.[18]

Joseph was also a weaver who did not use his trade.[19] He was first employed at Emu Plains, under Richard Fitzgerald.[20] The convicts assigned to Emu Plains were sent there long-term, as a means to instruct them in agriculture.[21] They cleared and cultivated the land.[22] On Bigge’s recommendation, parcels of land west of the Blue Mountains were granted to settlers to populate the area and raise sheep.[23] Joseph continued to work for Fitzgerald, taking charge of a grazing run near Bathurst, until he received a ticket-of-leave in 1829.[24] In 1837 Joseph received a Conditional Pardon.[25] Joseph farmed in the Mudgee area and died in 1850, aged 59, unmarried and childless.[26] Joseph was the product of the government’s plan and Bigge’s recommendations.

Isaac initially worked on road gangs, then as a shoemaker (his trade) with various employers in Sydney before road work again.[27] He absconded in 1829 and was described as a ‘troublesome character’.[28] In 1838 he received a ticket-of-leave.[29] Between 1841 and 1844 Isaac spent time in Newcastle, Darlinghurst and Parramatta gaols for drunken and disorderly behaviour, had a broken nose and scar on his face and had two tickets-of-leave cancelled.[30] He eventually received a Conditional Pardon in 1845.[31] The stints in gaol continued between 1860 and 1869 for drunkenness, assault of a woman, and vagrancy. By this stage he had an ‘F’ tattooed on his arm.[32] He spent time at Liverpool Asylum and died in 1872, aged 75, at the Lunatic Asylum, Parramatta.[33] Despite those with urban skills being more likely to marry than those in the textile industry, Isaac had not married nor had any children.[34]

It had taken decades for colonists to successfully grow crops and breed cattle.[35] Until 1820 convicts received salted meat. Bigge reported that convicts in 1821 received 7lb beef or mutton, or 4lb pork, 7lb flour, 1lb sugar, 3½lb maize and ¼lb tea.[36] Fresh meat was issued to the Farrars around a year into their sentence, thus improving their diet and health.

Convicts who arrived just years before the Farrars were paid by masters and could spend or save their wage. This was altered in the early 1820s following Bigge’s review.[37] The wage was replaced with remuneration of food, clothing and lodging. Earlier convicts also had a greater chance of receiving an early ticket-of-leave or other indulgence on the Governor’s approval, some issued just a few years into a sentence.[38] The difference between these (just) earlier convicts and the Farrars was the potential for earlier freedom, a difference in lifestyle, and potential to save money. John and Joseph received their ticket-of-leave after 10 years. 18 years after arrival Joseph received a Conditional Pardon. I have no record of John being issued one. Isaac received his first ticket-of-leave after 19 years. He had tickets-of-leave cancelled and reissued following his offences. 26 years after arrival he received his Conditional Pardon. Isaac was an example of Bigge’s punishment model, whereby convicts who offended could be downgraded to road gangs, and as a result, served longer than they otherwise might have.[39]

John, Joseph and Isaac came from the same English village, they had the same upbringing, were criminals together, were trialled and sentenced together and transported together. The only differences were their ages and occupations, yet their lives were so different.

The lives of these convicts were determined by the circumstances of a seven-year time period of great change. The end of the Napoleonic Wars, the introduction of ships’ surgeons, the opening of Hyde Park Barracks, and the implementation of Bigge’s recommendations all played a part in the direction of the Farrars’ life courses. Convicts who had arrived in the years just before the Farrars had the opportunity for a less restrictive lifestyle, earlier indulgences and perhaps freedom soon after arrival. John and his brothers were now ‘kept’ for longer periods. Their lives could have taken a whole different direction had they arrived even five years earlier. I believe they demonstrate that there is no such thing as a typical life course.

Do you have a convict ancestor? Find out how I can help with your convict research; see the Bottle Brush Package for more details.

Note: this is an essay I wrote and there is so much more information available, but due to the word limit imposed, it has not been included. If you are researching John Farrar, please contact me.

Bibliography

‘1828 New South Wales, Australia Census (TNA Copy)’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 5 May 2014.

‘Australian Convict Transportation Registers – Other Fleets & Ships, 1791-1868’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 5 May 2014.

Australian Dictionary of Biography, ‘Bigge, John Thomas (1780-1843)’, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/bigge-john-thomas-1779, Accessed 16 June 2020.

Deceased Estate File Joseph Farrar, New South Wales State Archives and Records.

Digital Panoptican, ‘Transportation’, https://www.digitalpanopticon.org/Transportation, Accessed 29 June 2020.

Harman, Kristyn, ‘Convicts’ Food and Diet’, HAA105, Module 4, Chapter 3, Accessed 8 June 2020.

Leeds Intelligencer.

Marriage index, ‘Australia, Marriage Index, 1788-1950’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 8 March 2020.

Maxwell-Stewart, Hamish, ‘Convict Occupations and Age Profiles’, HAA105, Module 3, Chapter 3, Accessed 29 May 2020.

Maxwell-Stewart, Hamish, ‘Convict Transportation from Britain and Ireland 1615–1870’, History Compass, Vol. 8, Issue 11, 2010, pp. 1221–1242.

Maxwell-Stewart, Hamish, ‘Height and Native Place’, HAA105, Module 3, Chapter 2, Accessed 29 May 2020.

Maxwell-Stewart, Hamish, ‘”Those Lads Contrived a Plan”: Attempts at Mutiny on Australia-Bound Convict Vessels’, International Review of Social History, doi:10.1017/S0020859013000308, p.10.

‘New South Wales and Tasmania, Australia Convict Musters, 1806-1849’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 13 April 2020.

New South Wales Government Gazette.

‘New South Wales, Australia, Colonial Secretary’s Papers, 1788-1856’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 4 August 2019.

‘New South Wales, Australia, Convict Indents, 1788-1842’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 5 May 2014.

‘New South Wales, Australia, Convict Registers of Conditional and Absolute Pardons’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 17 April 2014 and 13 April 2020.

‘New South Wales, Australia, Gaol Description and Entrance Books, 1818-1930’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 12 April 2014, 15 April 2020 and 1 July 2020.

‘New South Wales, Australia, Settler and Convict Lists, 1787-1834’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 18 August 2019.

‘New South Wales, Australia, Tickets of Leave, 1810-1869, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 8 March 2014.

‘New South Wales, Census and Population Books 1811-1825’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 19 April 2020.

Project Gutenberg Australia, ‘Report on State of the Colony of New South Wales’, http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks13/1300181h.html, Accessed 30 June 2020.

Registrar of Births, Deaths and Marriages, New South Wales.

Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, New South Wales.

Rylstone District Historical Society, ‘Joseph Farrar and John Farrar’, http://www.rdhswiki.com/page/Joseph+Farrar+%26+John+Farrar, Accessed 14 April 2014.

Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser.

Sydney Morning Herald.

‘UK, Royal Navy Medical Journals, 1817-1857’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 11 April 2020.

Yorkshire Parish Records, Yorkshire, England, page 192, unnumbered, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 12 March 2016.

Yorkshire Parish Records, Yorkshire, England, unpaginated, unnumbered, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 4 March 2015.

Footnotes

[1] Baptism of John Farrar, baptised 15 October 1800, Yorkshire Parish Records, Yorkshire, England, page 192, unnumbered, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 12 March 2016; Baptism of Joseph Farrer [Farrar], baptised 25 April 1791, Yorkshire Parish Records, Yorkshire, England, unpaginated, unnumbered, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 4 March 2015.

[2] ‘Criminal Court’, Leeds Intelligencer, 27 July 1818, n.p.

[3] ‘Criminal Court’.

[4] John Farrar and Isaac Farrar, John Barry, 1819, Convict Transportation Registers, The National Archives, Kew, Surrey, England, HO 11, ‘Australian Convict Transportation Registers – Other Fleets & Ships, 1791-1868’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 5 May 2014; Australian Dictionary of Biography, ‘Bigge, John Thomas (1780-1843)’, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/bigge-john-thomas-1779, Accessed 16 June 2020.

[5] Joseph Farrar, Grenada, 1819, Convict Transportation Registers, The National Archives, Kew, Surrey, England, HO 11, ‘Australian Convict Transportation Registers – Other Fleets & Ships, 1791-1868’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 5 May 2014.

[6] Project Gutenberg Australia, ‘Report on State of the Colony of New South Wales’, http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks13/1300181h.html, Accessed 30 June 2020.

[7] John Farrar and Isaac Farrar, John Barry, 1819, Admirality and Predecessors: Medical Journals, ADM 101. The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, ‘UK, Royal Navy Medical Journals, 1817-1857’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 11 April 2020.

[8] John Farrar, John Barry, 1819, State Archives NSW, NRS 12188, pp. 390-391, ‘New South Wales, Australia, Convict Indents, 1788-1842’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 5 May 2014.

[9] Project Gutenberg Australia, ‘Report on State of the Colony of New South Wales’.

[10] Digital Panoptican, ‘Transportation’, https://www.digitalpanopticon.org/Transportation, Accessed 29 June 2020.

[11] Project Gutenberg Australia, ‘Report on State of the Colony of New South Wales’.

[12] John Farrar, Indent.

[13] John Farrar, John Barry, 1819, Population Musters, Dependent Settlements, Series NRS 1264, State Records Authority of New South Wales, ‘New South Wales, Census and Population Books 1811-1825’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 19 April 2020; John Farrar, John Barry, 1819, Settlers and Convicts, New South Wales and Tasmania, The National Archives, Kew, Surrey, England, ‘New South Wales, Australia, Settler and Convict Lists, 1787-1834’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 5 May 2014; John Farroll [Farrar], John Barry, 1819, HO 10, The National Archives, Kew, Surrey, ‘New South Wales and Tasmania, Australia Convict Musters, 1806-1849’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 13 April 2020; John Farrer [Farrar], John Barry, 1819, Home Office, Settlers and Convicts, New South Wales and Tasmania, The National Archives, Kew, ‘1828 New South Wales, Australia Census (TNA Copy)’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 5 May 2014.

[14] Hamish Maxwell-Stewart, ‘”Those Lads Contrived a Plan”: Attempts at Mutiny on Australia-Bound Convict Vessels’, International Review of Social History, doi:10.1017/S0020859013000308, p.10.

[15] John Farrar, John Barry, 1819, State Archives NSW, Series NRS 12202, ‘New South Wales, Australia, Tickets of Leave, 1810-1869, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 8 March 2014; Marriage of John Farrell [Farrar] and Ann Neil [O’Neil], married 12 October 1832, ‘Australia, Marriage Index, 1788- 1950’ (Index only; no image currently available), Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 8 March 2020; Death certificate for Hannah Shanklin, died 10 February 1872, Registrar of Births, Deaths and Marriages, New South Wales, 6494/1872; Death certificate for John Farrer, died 2 November 1903, Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, New South Wales, 1903/015637; Death certificate for William Farrar, died 13 March 1913, Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, New South Wales, 1913/4158.

[16] Hamish Maxwell-Stewart, ‘Convict Transportation from Britain and Ireland 1615–1870’, History Compass, Vol. 8, Issue 11, 2010, pp. 1234–1235.

[17] New South Wales Government Gazette, 13 November 1839, n.p.

[18] Affidavit of Hannah Shanklin, Deceased Estate File Joseph Farrar, New South Wales State Archives and Records.

[19] Joseph Farrar, Indent.

[20] Joseph Tanar [Farrar], Grenada, 1819, State Archives NSW, NRS 937, p. 3, ‘New South Wales, Australia, Colonial Secretary’s Papers, 1788-1856’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 4 August 2019.

[21] Project Gutenberg Australia, ‘Report on State of the Colony of New South Wales’.

[22] Project Gutenberg Australia, ‘Report on State of the Colony of New South Wales’.

[23] Project Gutenberg Australia, ‘Report on State of the Colony of New South Wales’.

[24] Joseph Farrell [Farrar], Grenada, 1819, Settlers and Convicts, New South Wales and Tasmania, The National Archives, Kew, Surrey, England, ‘New South Wales, Australia, Settler and Convict Lists, 1787-1834’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 5 May 2014; Joseph Farrar, Grenada, 1819, Settlers and Convicts, New South Wales and Tasmania, The National Archives, Kew, Surrey, England, ‘New South Wales, Australia, Settler and Convict Lists, 1787-1834’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 13 April 2020; Joseph Farrer [Farrar], Grenada, 1819, State Archives NSW, NRS 937, p. 404, ‘New South Wales, Australia, Colonial Secretary’s Papers, 1788-1856’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 4 August 2019; Joseph Farrer [Farrar], Grenada, 1819, Home Office, Settlers and Convicts, New South Wales and Tasmania, The National Archives, Kew, ‘1828 New South Wales, Australia Census (TNA Copy)’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 5 May 2014; Joseph Farrar, Grenada, 1819, State Archives NSW, Series NRS 12202, ‘New South Wales, Australia, Tickets of Leave, 1810-1869, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 8 March 2014.

[25] Joseph Farrar, Grenada, 1819, Card Index to Letters Received, Colonial Secretary, State Records Authority of New South Wales, ‘New South Wales, Australia, Convict Registers of Conditional and Absolute Pardons’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 13 April 2020.

[26] Rylstone District Historical Society, ‘Joseph Farrar and John Farrar’, http://www.rdhswiki.com/page/Joseph+Farrar+%26+John+Farrar, Accessed 14 April 2014; Affidavit of Hannah Shanklin, Deceased Estate File Joseph Farrar, New South Wales State Archives and Records.

[27] Isaac Farrar, John Barry, 1819, Class HO 10, The National Archives, Kew, Surrey, England, ‘New South Wales, Australia, Settler and Convict Lists, 1787-1834’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 18 August 2019; Isaac Farrar, John Barry, 1819, HO 10, The National Archives, Kew, Surrey, ‘New South Wales and Tasmania, Australia Convict Musters, 1806-1849’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 13 April 2020.

[28] ‘Principal Superintendent’s Office’, Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 17 February 1829, n.p.

[29] Isaac Farrar, John Barry, 1819, State Archives NSW, Series NRS 12202, ‘New South Wales, Australia, Tickets of Leave, 1810-1869’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 19 June 2020.

[30] ‘Domestic Intelligence’, Sydney Morning Herald, 17 June 1843, p.2; Isaac Farrar, John Barry, 1819, Gaol Description Book, State Records Authority of New South Wales, ‘New South Wales, Australia, Gaol Description and Entrance Books, 1818-1930’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 15 April 2014 and 12 April 2020.

[31] Isaac Farrar, John Barry, 1819, Card Index to Letters Received, Colonial Secretary, State Records Authority of New South Wales, ‘New South Wales, Australia, Convict Registers of Conditional and Absolute Pardons’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 17 April 2014.

[32] Isaac Farrar, John Barry, 1819, Gaol Description Book, State Records Authority of New South Wales, ‘New South Wales, Australia, Gaol Description and Entrance Books, 1818-1930’, Ancestry.com.au, Accessed 1 July 2020.

[33] Death certificate for Isaac Farrer, died 9 April 1872, Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, New South Wales, 1872/5880.

[34] Hamish Maxwell-Stewart, ‘Convict Occupations and Age Profiles’, HAA105, Module 3, Chapter 3, Accessed 29 May 2020.

[35] Kristyn Harman, ‘Convicts’ Food and Diet’, HAA105, Module 4, Chapter 3, Accessed 8 June 2020.

[36] Project Gutenberg Australia, ‘Report on State of the Colony of New South Wales’.

[37] Project Gutenberg Australia, ‘Report on State of the Colony of New South Wales’.

[38] Project Gutenberg Australia, ‘Report on State of the Colony of New South Wales’.

[39] Maxwell-Stewart, ‘Convict Transportation from Britain and Ireland 1615–1870’, p. 1232.